- October 28, 2021

- Industry, Marine News

- The U.S. and Short Sea Shipping

“Virtues are lost in self-interest as rivers are lost in the sea”

Francoise de La Rochefoucauld, 1613-1680

Ships, on a cost-per-ton mile, are the most efficient way to move large quantities of material, raw or finished. But ships are useless unless they have somewhere to load and unload cargo.

In the name of efficiency, economies of scale have taken over many sectors of the marine industry. Larger ships, with no increase in the size of the crew, have decreased the per unit cost of cargo being shipped. From planning to delivery, a new ship can be put in service in two to four years.

The catch is that while the great new state-of-the-art ship is ready, the rest of the world’s goods distribution system may not be.

With the goal of the IMO and individual countries trying to reach Green House Gas (GHG) reduction goals by 2030 and 2050, ships with 20-year economic lives are being built now to operate on fuels of the future. This extra investment is an expensive gamble by vessel owners and operators.

The near future is about LNG, and LNG refueling infrastructure is being built at major ports throughout the world. But LNG, as it is currently being produced, is not the needed clean fuel. The future lies with green methanol, green ammonia, fuel cells and renewable electric power. These green fuels will have to be produced via renewable power such as wind, solar or even hydropower. This will take more years of study, testing, and then production. But will these fuels be available where they are needed?

The problem is port and inland infrastructure. While the 22,000+ TEU container ship is the height of efficiency there are a limited number of ports in the world that can receive these ships. It is not only that they need multiple new generation container cranes that can reach 22 to 24 rows of containers, such as is the arrangement on the largest container ships, but the entire port must fit the capacity of the crane(s) as well as the ships that bring the containers.

To receive the largest container ships, port facilities must have a water depth (preferably at Mean Low Water-MLW) above 51 feet. Post-Panama and Neo-Panamax ships of 6000 to 8000 TEU require water depths of 45’ to 50’. These ports also need multiple ship berths, from 800’ to 1000’ in length that can fit and hold such ships alongside. In addition, the berths must be strong enough to support several Super Post-Panamax container gantry cranes. These cranes can weigh over 1600 metric tonnes each and require additional electrical power to operate.

All this only gets a container off the ship and on to the dock. The more containers that are dropped in a port by a single ship the more container volume that must be moved within and in and out of the port. This calls for tractors and flatbed trailers, gantry cranes, both rail and rubber tired, straddle carriers, forklift stackers, and automation equipment. Plus, truck and rail transportation to move the containers from the port to their destinations.

Designing and building modern container ships can take two to three years. A permit for dredging or a bond issue for funds for port expansion can take two to four years before any actual work gets started. Expanding a container facility with additional land can take up to 10 years. While a ship can be sold off around the world, if a port doesn’t attract the business it needs to pay off its expansion debt, a governmental entity may be forced take at least part of the financial hit.

While ship funding can be risky, marine infrastructure funding may even be a tougher call. On top of port capacity, tomorrow’s most desirable ports will also have to have fueling capacity for vessels of all types running on LNG, ammonia, methanol, and other fuels that will become more common in the next decade.

The future seems to suggest a cap on container ship growth in the range of 24,000 TEU’s and this only for a restricted number of ships for the Asia-Europe trade where there are ports and some infrastructure (Europe’s existing inland and coastal short sea shipping distribution system) which can handle the load. Most of the rest of the world will be living with variations of a hub-and-spoke system with 8000-12000 TEU ships calling at select ports while feeder ships of smaller capacity, and inland transportation, completing the distribution of the containers.

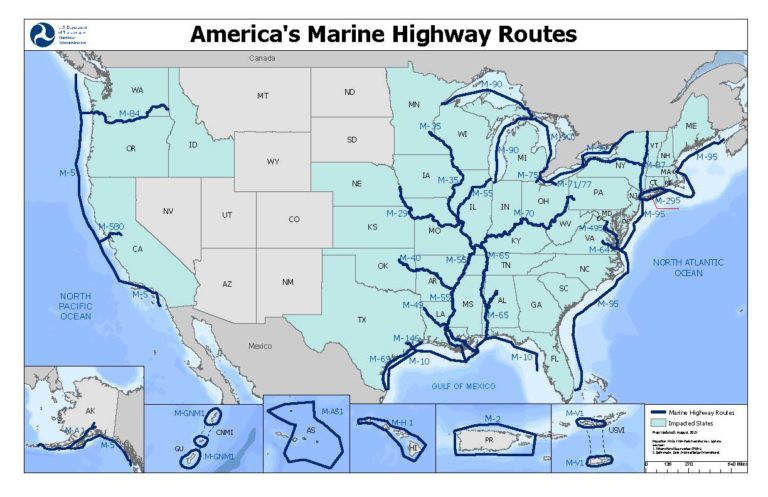

In the United States part of the move to assist waterborne distribution of cargo is the America’s Marine Highway System (AMHS). In Europe 40% of cargo is distributed by water. In the US, only 6% is moved by water while 75% is via truck. Admittedly, this is because much of the US is not economically accessible via water while much of Europe has an infrastructure of navigable rivers, locks, and canals.

The AMHS was set up by Section 1121 of the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007. Its purpose was to reduce fuel consumption and road congestion by facilitating more tons-per-cargo-mile efficient barge and ship movements. This use of more marine assets would also support US long term security plans by maintaining a Jones Act fleet and necessary shipyards. While originally meant for container movements, Section 405 of the Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation Act of 2012 opened support for movements of some break bulk cargo, like project cargo, and roll-on/roll-off including ferries.

While somewhat originally limited to the U.S. East Coast and inland rivers, it has since been expanded to cover 26 routes which includes all four of the US coasts plus non-contiguous areas like Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and Guam.

AMHS isn’t cheap and isn’t entirely successful. Container movements via tug-barge between Baton Rouge/New Orleans and Norfolk/Richmond are proving to be successful. DLS Marine’s Norfolk office provides marine survey services for many tugs on the Norfolk/Richmond route. Other container routes are improving as increases in efficiency and efficiency of scale bring down direct costs. However, studies have shown that the indirect costs of truck wear on infrastructure roads and bridges along with fuel cost and pollution make the AMHS a long-term money saver.

Altering historic transportation routes is not easy. The Railroad and trucking industries have powerful well-funded lobbies and tariff manipulation is not unknown. The rail and barge industry had tariff wars in the days of coal delivery to coal fired power plants. On top of that, the Harbor Maintenance Fee (HMF) levees a fee on each container move in each port. If a container is moved from a ship to a barge in one port then moved to a second port and unloaded there, the HMF is paid twice, increasing the cost of transportation.

As an aside, you will note that it is a fee and not a tax. The harbor fund has billions of dollars in it as Congress has loved collecting it but not spending it as the surplus makes the “books” look better. While it may be unreasonable to “tax” a container twice, someone else pays it and the government benefits. Marginal benefits trickle down to the ports themselves as the fund pays for dredging up to 50 feet. But dredging over 50 feet, the port must pay half of the additional cost for the additional depth. And as noted above, the largest container ships need more than 50 feet.

While the government wants the benefits of AMHS, it doesn’t want to give up the benefits of HMF which would make the financial end of the American Marine Highway System more palatable.

As part of the 2012 Act, the Maritime Administration (MARAD) was requested to design an ATB container barge. The only outcome we have found was a conceptual design from the Ocean Tug & Barge Engineering Corporation apparently done for the Maine Port Authority and McAllister Towing & Transportation Company. The tug is a standard design at 139’ with possibly 6000 hp from three EMD dual fuel engines. The proposed barge would be an open hopper design with a length of 507’ and a capacity of 894 TEU. Several sections will have adjustable fittings for 48’ and 53’ containers and the barge will have machinery flats to support reefer containers. We haven’t been able to find out if any work on this design has gone forward.

Speaking of Dual Fuel

A Norwegian company that is already involved with LNG fueled vessels has announced that it will convert one of its existing OSVs to green ammonia. This with the participation of Wartsila and EU funding. The Europeans are further along in research and development on new fuels due to the active financial support of the EU and individual countries. These experiments must be pushed along if the industry is going to meet the IMO and EU pollution reduction deadlines.

While the bright light is on designing engines to run on the fuels of the near future, and to provide on shore and onboard delivery systems for the fuels, the engine lube oil manufacturers have no idea what products they will have to produce. Their R&D has to be done hand in hand with the R&D of fuel and engine companies to see the long-term effect of each fuel on the properties of the lube oils in each engine design.

Compliance with IMO regulations on emissions, ballast water, and biofouling has created a cost domino effect for operators and charterers. For now, the replacement cost of a compliant vessel will be the benchmark for its value as the acceptance and desirability for various green designs has not been shown in the marketplace. In the future, the right guesses on compliance may be the ones that create the market benchmarks and the wrong guesses the unwanted stranded asset.

The DLS Marine team of ASA certified marine appraisers, through our long relationships with owners, lenders, shipyards, and designers, will closely follow these unprecedented changes in the marine industry, domestically and worldwide. Through these close ties we will continue to provide accuracy on the technical and valuation sides for our customers.

-Norman Laskay

If you’d like to keep this conversation going, please email me at nlaskay@DLSmarine.com