- November 15, 2022

- Industry, Marine News

- Who’s In Charge Here?

“Give me an ultra-fast algorithm for I intend to go into harm’s way.”

R.A. Ornelas

Ocean Master & Pilot Unlimited Gross Tonnage, Retired

AUTONOMOUS VESSELS and FLOATING WIND FARMS

As pointed out in past blogs, technology is advancing at a swift pace powered by ecological regulations and ESG investments; however, laws (particularly Admiralty laws) can’t advance at such a pace.

The state of maritime law as it pertains to these new areas of the marine industry is very important to lenders, lessors, and marine underwriters. What does the insurance policy cover and who is/are the beneficiaries? How can a lender protect their position? Here are some things to consider:

AUTONOMOUS VESSELS

There are various levels of autonomy and there doesn’t seem to be full agreement by interested parties on what they are.

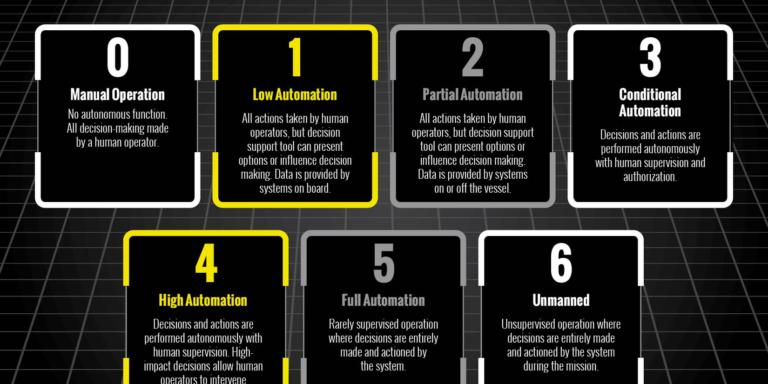

Per Sea Machines, a U.S. technology company involved with autonomous vessel systems, Lloyds Register gives six levels of autonomy:

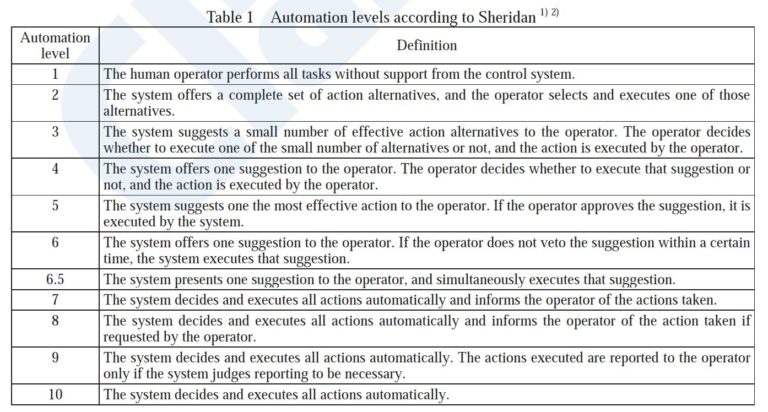

The ship classification society Nippon Kaiji Kyokai (known as ClassNK) has ten levels:

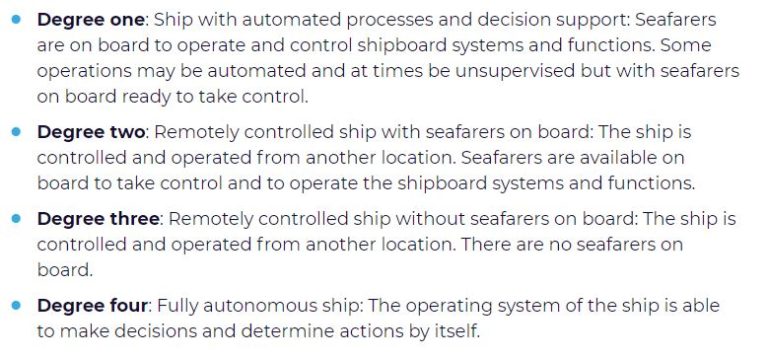

As a work in progress, the IMO under the MSC group has been conducting a regulatory scoping exercise for Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS) and are presently thinking of establishing four levels of autonomy:

Bureau Veritas has four levels of autonomy, ABS appears to have three (although they talk about a 4-step maturity level), and DNV has five.

For quite a while, underwriters will measure risk by attorney’s fees.

After sitting in on a webinar with a panel of international attorneys and legal academics, I learned about some of the problems that will be faced by owners, operators, insurers, and port state authorities. Some seem solvable in the short run but others, such as clearer regulations by IMO and maritime states/flag states and their port state authorities, can take years to enact and years of legal precedent to clarify.

Admittedly, most of these difficulties will arrive when autonomy reaches levels 3 and 4, and some of these may be worked out in the intervening years, but as with decisions on investing in what fuel, contracts, and policies are in place, the decisions have to be made before a ship even hits the water.

Thoughts…

- Where there is vessel traffic control and/or lane separation, who do authorities contact when there is no one onboard?

- What is the chain of command in case of an accident when there is no Master or crew to hold accountable? Flag state? Owner? The Management Company? The “driver” 2,000 miles away? Currently, authorities will often arrest the Master and possibly some crew members on scene. With autonomy, they no longer would have that leverage.

- Who is the Master when the absentee operators work in 8-hour shifts? Just the one on watch at the time of the accident? What if a situation started on one shift and ran over into the next?

- Some flag states have already stated they will not recognize autonomous ships. In others, their state definition of “ship” or “vessel” would prohibit MASS as the definitions often include mention of crew. This same definition problem arises, as any new international regulation covering MASS would have to span the differing definitions of “ship” and “vessel”.

- Class societies do have some standards for onboard AI equipment and will have to be working towards more standardization of such equipment and their algorithms with the backing of IMO and authorities such as USCG.

- Who will develop, certify, and inspect the shoreside operation?

- The International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW) provides operating crew standards, and port state authorities require specific crewing sizes. MASS vessels are not in accordance with either of these. They conflict with crew size requirements and put in question the requirement for a “proper lookout by sight and hearing”.

- What should be the qualifications and training of the shoreside operator? Should they have a marine background or can one learn as with a digital game, i.e., simulators?

- In the case of a pollution incident, will the vessel’s mandatory oil pollution coverage (required by many port states) cover MASS?

- For port states to protect themselves from pollution or wreck removal, will ships be required to post a large bond before they can enter the port or even transit territorial waters?

- What if the shore operator is in a country that is not an IMO maritime country and does not have to follow regulations? This might be like another form of Flags of Convenience (FOC).

- What about the future of passenger ships without navigating crews? Will people feel safe on board? It is happening now, but typically on ferry boats that are never out of sight of land. Are cruise passengers ready to sit at the Captain’s Table with HAL 9000 or C-3PO? (probably).

Committees of ship operators, port state authorities, underwriter groups, lenders, naval architects, and shipbuilders, are all meeting to see how MASS fits into their future. Answers will be complex, elaborate, confusing, and a long time coming.

FLOATING WIND TURBINES

Floating wind turbines don’t have the legal entanglements that autonomous vessels have – yet.

Floaters (as floating wind turbines are referred to), are presently recognized as vessels for class purposes and fall under the same regulations as MODUs (Mobile Offshore Drilling Units) and FOFs (Floating Outer continental shelf Facilities). They will be subject to annual, interim, and the five-year special survey. A few specific parts, like tethers (the turbine anchoring system) will only be inspected every five years. As they are unmanned, they are not subject to regulations pertaining to crewing and safety and domestically, they do not need Coast Guard COI’s. If they are legally perceived as “vessels”, they are subject to being registered by their flag state and thereby subject to a maritime mortgage. This is presently in effect in Norway.

Floaters are being installed in deep water areas around the world. They may soon be used in New England, the U.S. west coast, and off the continental shelf in the Gulf of Mexico. Any domestic use may be a lift for GOM fabrication yards with their long experience in building offshore floating structures, anchor systems, and tethers.

One can see that an annual inspection of an offshore array of a 50-unit floating wind farm will be quite an undertaking. DLS Marine has been ahead of the curve, being the first independent marine survey company in the U.S. to be certified by ABS for the use of drones for remote inspections. Since then, we have continued our involvement through our affiliate company DroneUp, doing test drone inspections with Dominion Energy on their first Virginia offshore fixed turbines. We continue to work on software specially for drone turbine inspections and the production of digital reports of the inspections that will satisfy the needs of owners and regulatory bodies.

Legal entanglements regarding floating wind turbines are inevitable. Assuredly, there will be pressure applied by interested parties to alter the definition of a floater away from being classified the same as a vessel in areas where they are legally recognized as such. Also, lenders may start pushing back to maintain a straightforward means of loan security.

Other News

Choosing Fuels

Marine equipment of the future will have to be diversified. When it comes to traditional marine fuels, it has always been “one size fits all” with engines sized for the vessel, and while that is still true, now there is an additional challenge to accommodate the requirements for new fuels as well. Conveniently, LNG and Ammonia carriers can operate on the boil-off from their cargo, so the energy level of the fuel is not as important as with other vessels.

The power density of fuels now must fit the vessel’s service. A low power-to-weight fuel like hydrogen best fits short travel craft like ferries and other harbor vessels. They can refuel frequently through close fueling sites or swapping out tanks. This improves fuel efficiency by avoiding the need for large and heavy fuel tanks which add to overall weight. Power density is also a factor with large ocean service vessels. These vessels must sacrifice cargo capacity to accommodate the requirements of future fuels.

Aside from LNG, there is methanol which has a high power-to-weight ratio and is carried as a liquid. Rolls-Royce/MAN has developed methanol engines currently being installed on a large yacht. They state that there are 70 methanol engines on order. This is preliminary, with visions to produce larger engines for larger ships.

To be kept in mind, whatever fuel is being used in the main engines(s) should also work in the generators. Some of the new fuel engines are being perfected in smaller engines such as generators and have not had enough testing to justify the expense of building bigger engines for that fuel. This hurdle is somewhat avoided in diesel electric vessels.

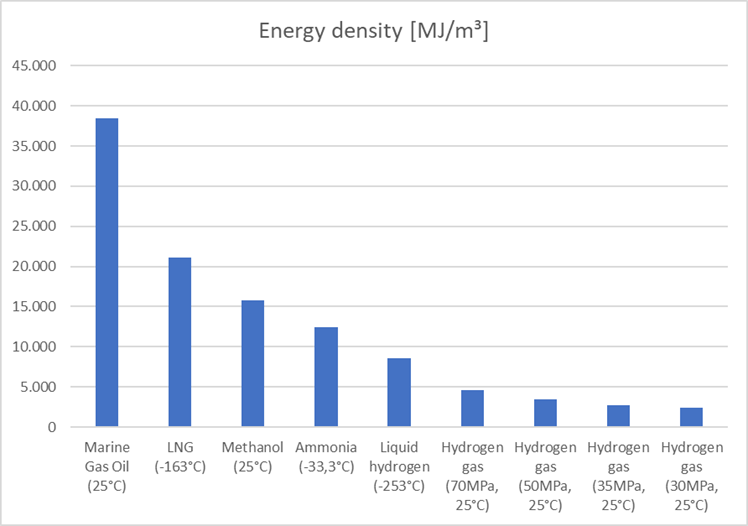

Here is a reminder of the trade-offs with which owners are dealing:

This chart shows that, of the alternative fuels, LNG is the best in energy density. It is cleaner than traditional marine fuels and readily obtainable. This is despite the additional cost for LNG fuel storage and its required supply systems onboard ships. With world affairs affecting the market, the cost of LNG has made it less attractive. Methanol can be handled at closer to normal temperatures, but you need twice the amount. The same back and forth trade-offs fit all the fuels.

According to a new BV White Paper, here are the Well to Wake (WtW) pollution tradeoffs of marine fuels. Boardroom decisions aren’t getting easier.

Engine Innovation

In the past I have mentioned that while most of the environmental regulations are coming out of the Euro bloc and affect blue water shipping, domestic companies compete worldwide and must comply with these regulations to be competitive. Among these, Cummins has three marine engines that are built to satisfy international regulations – The 1000-1500 HP QSK-38 Tier 4 is IMO III compliant, the 1400-2200 HP QSK-50 is IMO Tier II compliant, and the 2000-2700 HP QSK-60 is IMO III compliant. Cummins also has hydrogen and hydrogen cell engines for industrial and trucking use. There will be some future adaptation for marine use in smaller vessels. Caterpillar’s large marine engines – the 3512E Tier 4 Final, 3516E Tier 4 Final, and the C32 Tier 4 Final are all IMO III. For now, it appears that their alternative fuel offerings are only for the generation of electricity. Cat’s subsidiary, ProgressRail, produces the EMD E23 B 710 at 5000 HP which is IMO III.

Domestic engine innovation is in the lower horsepower engines and mainly for fixed power units and some over-the-road engines, whereas all large blue water engines are provided by foreign engine manufacturers. All manufacturers are facing decisions on where best to compete as there are 2-stroke and 4-stroke engines, high speed and low speed, and multiple fuels to run them. The builders of the large engines have gone to modular designs where the engine is standard but can be adapted to varying and dual fuels by “bolt on” injector and rail systems that can meter different fuels and controllable turbochargers. In addition, makers of lube oils have their own R&D to provide lubrication that stands up to the profiles of the different fuels.

Engine failures due to improper procedures in fuel changeovers have been expensive to operators and underwriters. This is another learning curve for the industry.

-Norman Laskay

If you’d like to keep this conversation going, please email me at nlaskay@DLSmarine.com

Footnote 1:

The quote at the head of this blog was spotted in the Comments section of an article that I read several years ago about autonomous vessels. It was such a great example of the dry humor I have heard from experienced mariners over the years that I had to add it to my interesting quotes file. If I ever meet Captain Ornelas, I would be glad to share my grog ration with him.

Footnote 2:

The cartoon is the product of Ms. Bonnie Taylor, ex Caterpillar Financial Services Nashville, ex customer and now friend. In her retirement she paints and answered my call to draw up a cartoon. Happily, we have a sample of her real work, a painting of a rural European village street, hanging in our house.