- January 23, 2024

- Industry, Marine News

- CURRENT BATTERY SCIENCE IN TRANSPORTATION and AN ONGOING LOOK AT INLAND

“We will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles.”

-Thomas A Edison

In September 2021, I looked at the growing use of Lithium-Ion batteries in forms of transportation. It was researched for my own education as well as for my readers. This blog will try to give basic information on the new generation of batteries and the systems that will be necessary for them to be used in various types of transportation as stored electrical power starts to take over from fossil fuels.

There are many new types of batteries, and the desirability of any type will come down to their intended use. The battery type that works well in a laptop or in an automobile may not suit other uses. But the fact remains that every asset that currently uses fossil fuels will be impacted by the use of electrical power from battery storage systems. Batteries provide instant power and nearly the output of the energy put into them. A quote by a Director of DNV, “You get almost the same energy out of a battery that you put in. In contrast, if we are talking about hydrogen, ammonia, or methanol, you put one Euro in and you get 20 cents back.”

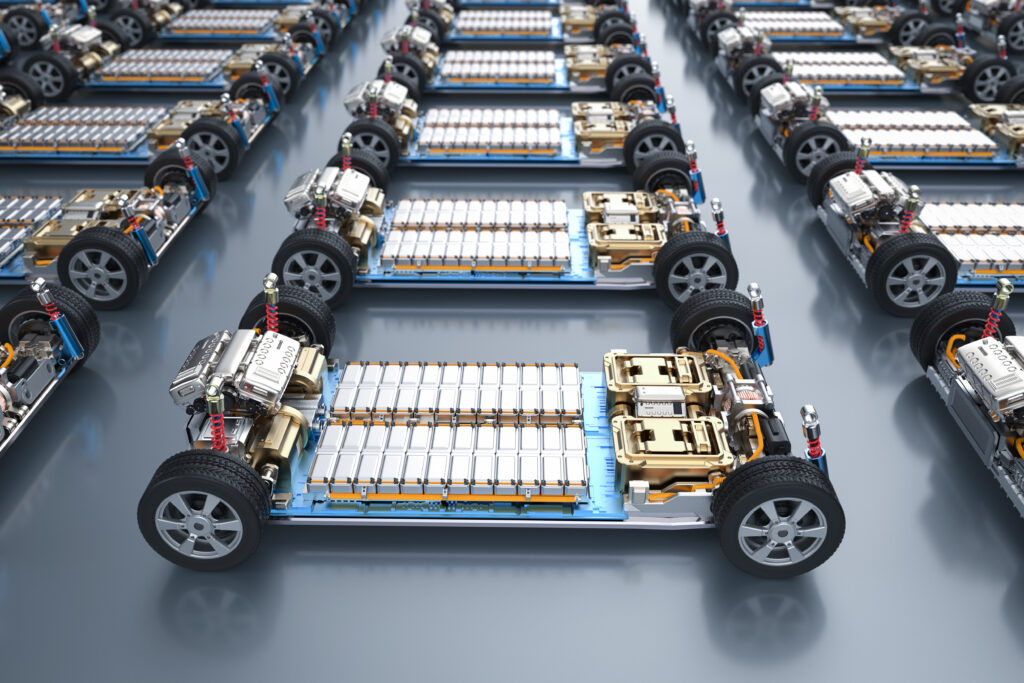

As a starting point, we’ll take a brief look at what Tesla has done in their 20 years of experience. They have three basic batteries, all lithium liquid anode type:

Nickel Cobalt Aluminum (NCA) High energy density

Nickel Cobalt Magnesium (NCM) High energy density

Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) Lower energy density

Cobalt is a major component of these batteries. The more cobalt, the more energy density. But a side effect is a reduction in control of lithium runaway, and it reduces the life of the battery. Substituting nickel or magnesium for part of the cobalt increases safety and reduces the cost, at the price of losing energy density. Energy density is the amount of energy a battery contains in proportion to its weight. This is given as Watthours per kilogram (Wh/kg). You will see this term used in the comparison of batteries for Electric Vehicles (EV).

To move a set weight a set distance, it will require either more lower energy density batteries, or fewer higher density batteries. The more batteries that are needed increases both the weight and the cost of the battery system. One can increase the energy density and life with newer type batteries, but with the tradeoffs of increased size/weight and cost. A 100 kWh (Kilowatt Hour: an accepted scientific form of measuring electrical energy as the energy delivered by one kilowatt of power for one hour) battery system that powers an EV currently weighs around 1,200 pounds (544 kilos). An increase in the size of the desired battery power increases the weight of the system, which increases the weight that must be moved and in turn decreases its life. The more power a battery produces through its instant torque, the heavier the various components of the propulsion system will have to be.

To further complicate which battery to use, different battery makeups will have different cycle lives. Normal LI batteries can last 3,000 to 5,000 recharging cycles depending on whether they endure light or heavy commercial use. Cycle life is also affected by high or low temperature use and how low you allow a battery to get before it gets recharged. There is also a “C Rate” factor to add, or how fast a battery can be recharged. For autos, they are rated C-1 to C-3 with C-3 being the fastest. But the faster the charging rate, the shorter the battery life.

Each battery must be monitored so that the user knows its present status and to not allow it to over discharge. The point of over discharge will depend on the type/design of the battery in use. Commercial boats and many pleasure boats already have such monitors for their lead acid battery systems. There are already large monitoring systems where multiple modern lead acid batteries are in use for large commercial backup systems or hybrid uses. The current term for such control systems is often Electrical and Electronics (E/E) system.

Adding to the technological complexity, large users, such as power plants and hybrid or electric powered ships, will have massive battery banks made up of blocks (comprised of small batteries) which can be added to or removed from a bank depending on the power output desired. Some of you may remember the Saturday Night Live spoof on a battery-operated car: SNL Mercedes Commercial. Humor aside, large commercial battery blocks will need high technology systems to monitor the status of each battery in each block in a battery bank.

Automobiles and trucks can work with current battery types. Fixed storage sites (used with solar and wind farm electricity) have the necessary space to handle new concepts for large and heavy battery banks that may in the future be produced at a reasonable cost. In marine use, however, vessels cannot use the benefits of current standard fixed systems. Ships need high density banks for long sea passages, along with reduced weight and size, so as not to reduce cargo capacity. They must also offer high safety, long life, and acceptable cost. Obvious challenges.

The above listed Lithium batteries are all of the liquid anode type. New science is exploring solid anode, i.e., solid-state batteries (SSB). Of great interest are the Lithium-Zirconium-Chloride (LZC) and Lithium-Lanthanum-Zirconium-Oxide (LLZO). They are attractive as they have higher power density, are easier to produce with more readily acceptable materials, and are therefore less expensive. Research is seeking more easily obtainable materials to lower costs and to help ensure a controlled supply chain. However, this is still early science as while the solid-state battery can be denser, safer, and cheaper, there are still ongoing problems with the solid electrolytes distorting or breaking. The search continues for the right combination of solid electrolyte material that will give SSBs acceptable useful lives.

Another option is the REDOX Battery (Reduction-Oxidation). They are not easy to describe in detail as they are two tanks of chemical liquids that are pumped through a membrane held by electrodes to produce electricity through a complicated scientific process. They are inexpensive and can be used in applications that can accommodate their larger size, a factor of their lower power density. They are best in a service with consistent draw.

The new era of Electrical and Electronics Systems (E/E), introduces new acronyms:

- REPS: Renewable Energy Power System – A standalone renewable energy site. Of great interest in rural areas as well as ships.

- ESS: Energy Storage System – A system that integrates a power source(s) (solar/wind) with battery storage and is used in a REPS. This can be the major cost in renewable sources such as solar panels where the cost of a panel is quite low when compared to a wind turbine.

- HESS: Hybrid Energy Storage System – A system that can be more efficient than ESS, is smaller, costs less, and has a longer life.

- RES: Reuseable Energy Systems – Systems that will integrate different renewable energy sources into a power grid.

- EMS: Energy Management Systems – Computerized tools for managing a grid.

- SMG: Shipboard Micro Grid – A grid that handles the input of any mixture of onboard energy sources. On ships, this could range from passive solar panels to wind, fuel cells, onboard generators, and flywheel shaft generators. An SMG may have its own flywheel energy storage system (FESS).

Besides control, a good E/E will also track the condition of all pieces of a system and provide information for planned maintenance or replacement. At the International Workboat Show, I saw some of the control/monitor systems that are made by BAE for hybrid vessel use, and they are extremely compact, being about the size of large home tuner amps. Of course, the larger the system the more control/monitor units needed.

We have gone over the current and future varied input sources. The electrical output needs on ships are not the typical 110V or 220V needs of a home. The electrical draw of ship equipment can vary greatly. Different radars and sonars have different and complicated pulse loads. Other electronics, such as communication and navigation, are more straight forward. Normal power plant loads will vary as any city grid draw will vary by day and night and weather. For a ship, the electrical demand varies depending on its service. A tug will have varying demands as it maneuvers in harbor while a ship at sea may have a steady demand for days as it crosses an ocean. However, in bad weather, the demand will vary constantly for days at a time when its propellor comes partially out of the water in heavy seas. Ships in port, while idle at the dock or at the dock working cargo, may have activity at one hatch or four hatches, ballast pumps and/or cargo heaters working, causing consistent fluctuating demands.

It seems like there are unending variables in producing the right sized system. On a yacht or for a home’s solar storage system, one adds up all the equipment and what they will draw, along with the length of time they may be drawing power. This same general idea is used for designing a REPS for ship service but with more complications.

In designing such a system, a major factor is cost. One calculation is Net Present Cost (NPC), a variation of the more familiar Net Present Value (NPV). Of major importance will be the calculation of the systems Normal Economic Life (NEL) and the ESS/HESS replacement cost at the end of life. An online search will give you more details on how NPC calculations are performed.

One estimate is that by 2030, electric and hybrid-electric systems will be normalized onboard ships thanks to advances in technology and affordability. For an industry that didn’t change significantly between 1940-1960, marine related technology is now advancing by the month towards feasible designs.

The world’s first 100% battery electric capable self-unloading limestone carrier is being built in Australia by Adelaide Brighton Cement (Adbri) in partnership with Canada Steamship Lines (CSL). Scheduled for delivery in 2026, this will be a hybrid vessel with 25% of the needed diesel power being repacked by electrical power. By 2031, the intention is to have the vessel entirely electrical.

A Japanese company, PowerX Manufacturing, is building a 459-foot battery tanker for service starting in 2026. This design is for the vessel to have onboard 96 containerized batteries. These batteries will be of the L-I type with full E/E systems and safety systems for gas emission control and fire suppression. The purpose of this design is to “fill” the batteries at a near offshore windfarm and to deliver the electric power to a shore station in areas in need of greater electrical supplies. As battery science improves the amount of electricity that can be transported will increase. This type of transportation is planned to replace more expensive and longer construction times for underwater cables and offshore substations.

AN ONGOING LOOK AT INLAND

The water depth of the inland rivers continues to affect cargo quantities carried. There have been some improvements with rainfall upriver, which NOAA futures indicate that water in these areas will fall again. Without the reassurance of water depths throughout an upriver or downriver passage, barges are continuing to be loaded to conservative drafts. We will see how the river conditions have affected bottom lines when we look at the 2023 financial records of inland operators like Kirby.

Of the two main grain commodities of corn and soybeans, corn exports are well above 2022 levels while soybeans are down. The good year for corn is not completely golden for barge operators as a fair amount of corn exports go to Mexico and most of that is delivered via rail.

With faith in the strength of the inland waterway market, Associated Terminals has asked the COE for permission to create a barge fleeting area near their present Convent, Louisiana site that will also include mooring of a 330’ x 75’ stevedoring barge.

As I mentioned in an earlier blog post, 2024-2025 will be active years for the renewal of USCG Certificates of Inspection (COI). According to Current Data LLC, 1,871 inland tank barges will need inspections and renewals which is 43.6% of the aggregate carrying capacity of these barges. (It is also reported that this new company is preparing data on the inland hopper barge fleet covering through 2023.)

The majority of inland tank barges operate on a five-year inspection cycle. Per Current Data LLC, renewals were done on 543 barges in 2022, 639 in 2023, and a proposed 1,008 in 2024. These numbers help indicate the years in which the river petroleum market was strong and when many new barges were built. We will see similar numbers in five-year cycles going forward. Five-year old barge inspections do not incur high costs as they generally only involve cleaning, drydocking, and the inspection (plus possibly a few desired upgrades). But older barges may also need steel and machinery repairs and/or repainting of the hull and topsides. Costs for older barges may therefore range from $100,000 to $200,000. In Kirby’s 2022 10-K, they note that future income will be affected by upcoming mandated maintenance costs.

While these statistics pertain to the barges, because of the USCG Subchapter M regulations that make most inland tugboats have COIs, such boats will be coming up for renewals spread over the three years that fleet owners had to get their entire fleet in compliance with the new regulations.

As this maintenance bubble comes along there are a fixed number of shipyards available to do this work and a reduced number of shipyard workers available so shipyards are battling among themselves for competent people. This will probably mean higher shipyard repair costs.

-Norman Laskay

If you’d like to keep this conversation going, please email me at nlaskay@DLSmarine.com